A few days ago, I finished the second draft of my novel, Virginia’s Ghost. I printed the whole thing out and have since started reading it again, scribbling notes in the margins about things I want to correct in the third draft. But more than correcting errors, I need to add much more detail. One storyline in the novel is set in 1928 Toronto, but when I was reading through the book, I was struck by how blandly generic my setting seemed. I could have been writing about almost any North American city in the twenties. Rather than writing about made-up places based vaguely on my impressions from Hollywood movies, I need to write about real places that existed in Toronto back then. And I need to learn a lot about these places, either by visiting them (if they still exist) or reading about them.

What better place to start than right in my own neighbourhood? A pivotal scene between my well-to-do young flapper Constance and her caddish boyfriend Freddy takes place in a park–but not just any old park. I’m rewriting the scene to take place in Craigleigh Gardens, just off South Drive in the South Rosedale area of Toronto. The present-day park was the original site of Craigleigh, a 25-room Victorian mansion that belonged to wealthy businessman Edmund Boyd Osler. He lived there from 1877 until his death in 1924, after which the house was torn down and the 13 acres of land it stood on were presented to the city as a public park. Below are the stately stone and wrought-iron gates to Craigleigh that were erected in 1903. If you look closely, you may be able to make out 1903 in gold on each gate between the two main pillars.

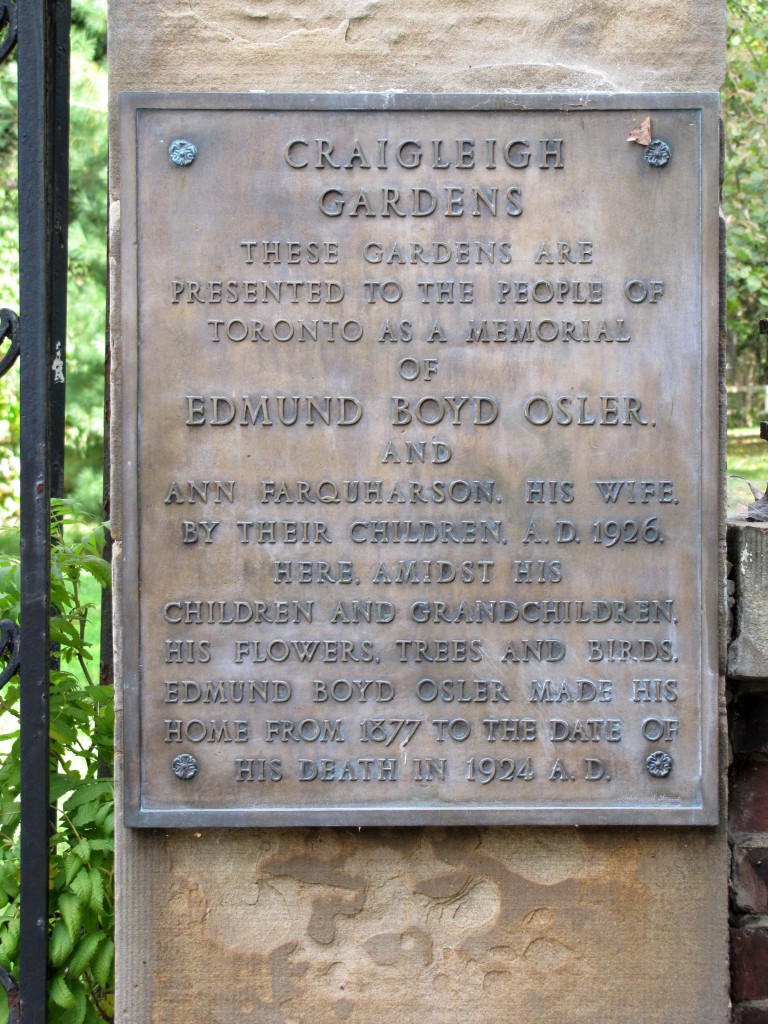

And here’s the plaque that commemorates the Osler family’s extraordinary gift to Torontonians:

And here’s the plaque that commemorates the Osler family’s extraordinary gift to Torontonians:

I’m fortunate enough to be able to treat myself to a walk in this lovely park almost every day. It’s airy and spacious, and it’s a wonderful place for my dog Trinka to romp and stomp and enjoy some precious off-leash time.

I’m fortunate enough to be able to treat myself to a walk in this lovely park almost every day. It’s airy and spacious, and it’s a wonderful place for my dog Trinka to romp and stomp and enjoy some precious off-leash time.

And as I walk through the park, which would have been quite new back in Constance and Freddy’s day, I now imagine the two lovers playing out one of the most emotionally wrenching scenes of their young lives before a cluster of colourful onlookers, all of whom have definite opinions about what’s taking place. Just knowing more about Craigleigh Gardens and experiencing the beauty of this place every day helps bring the scene between Constance and Freddy to life in my mind. I only hope that my experience will translate into writing that vividly brings it to life for my readers.

Follow

Follow