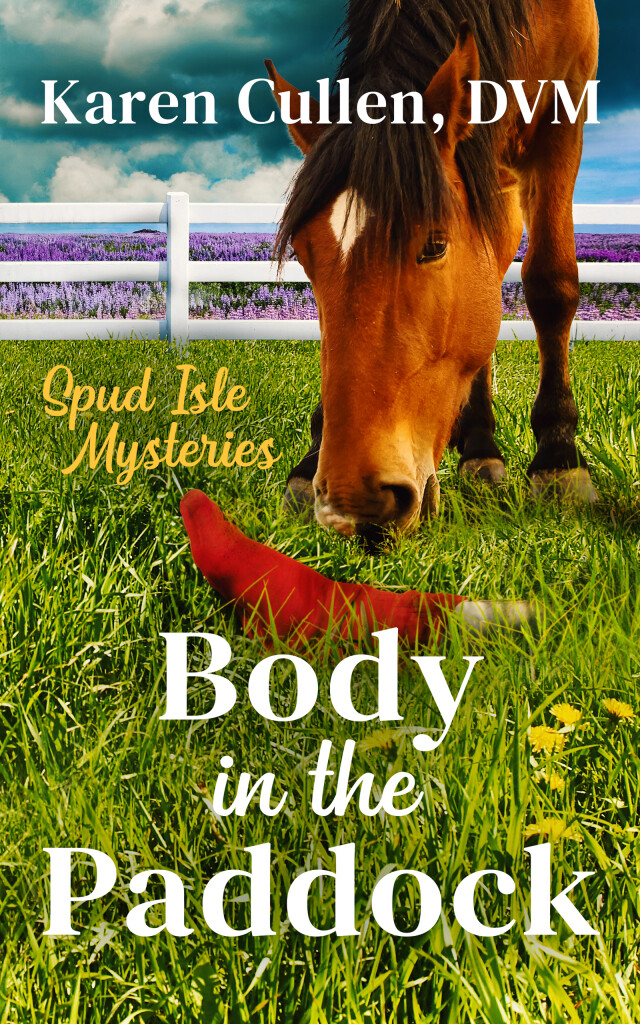

Delightful author Karen Cullen recently released an equally delightful cozy mystery entitled Body in the Paddock, which features intrepid student journalist Fran Fitzpatrick. I sat down with Karen to chat with her about her new novel, as well as Breeding Trouble, her previous book.

Caroline: I absolutely loved Fran Fitzpatrick, the protagonist of Body in the Paddock. She’s determined, hilarious, sometimes socially awkward, and a bit klutzy too. And her heart is always in the right place. How did you come up with this character? Does she resemble anyone you know?

Karen: Fran’s relationship with Aunt Josephine and Uncle Johnny is loosely based on my relationship with the aunt and uncle I lived with during my first two years at UPEI, but that is where any resemblance to real people ends. While I tend to use humour in a stressful situation the way Fran does, Fran is completely fictional—she is not based on any particular person.

Caroline: Your novel is set largely on the University of PEI campus, where Fran attends classes—when she’s not too busy solving mysteries! Why did you choose to set the novel in PEI? Tell me more about your connection to the Island.

Karen: I choose the University of Prince Edward Island as the setting for Fran’s adventures because it is my alma mater. My intent when I first registered at UPEI in the mid 1980s was to study English literature with the goal of eventually becoming a journalist. When I was informed by a relative that a veterinary college was soon to open on the UPEI campus, I changed my major to my other interest—veterinary medicine. During one of my “pre-vet” years, I was the photographer and an occasional writer on our campus newspaper, The Netted Gem. I also had a show on the school’s radio station. I thought it would be fun to write a story loosely based on my time as a student at UPEI. I say loosely because, thankfully, there were no murders during my time there.

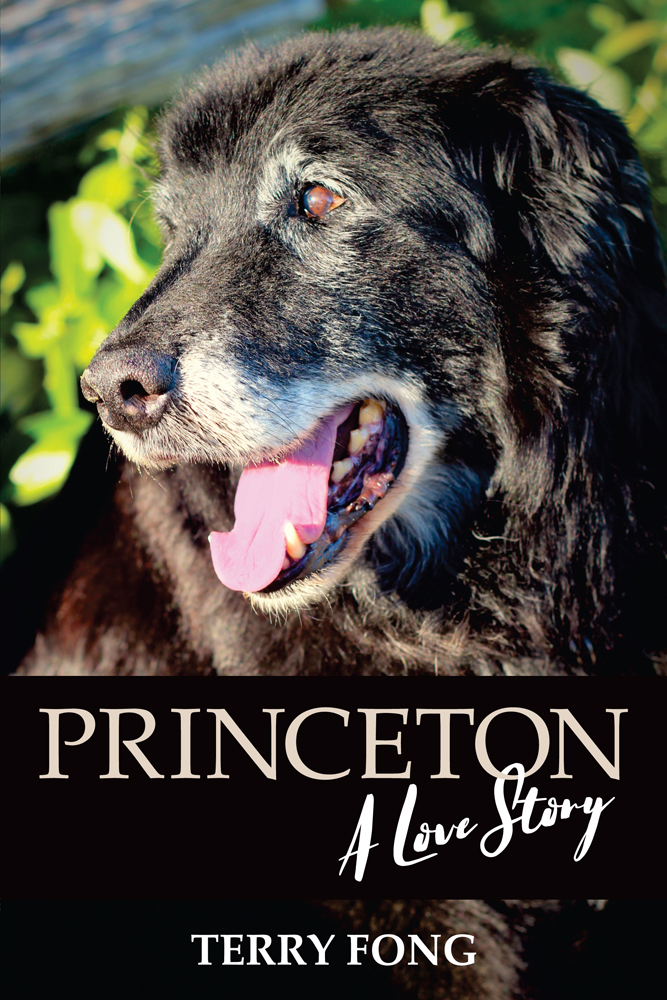

Caroline: In your non-writing life, you’re a veterinarian. How have you brought your science background and experiences as a veterinarian into writing fiction? I’m thinking especially of your first book, Breeding Trouble, but also of Body in the Paddock.

Karen: My first novel, Breeding Trouble, is centred on the heroine’s work life as a veterinarian. It felt natural to include a glimpse into the real world of veterinary medicine—cases, patients, clients, and clinic staff. While the individuals featured are completely fictional, some of the cases presented are based on real cases and patients I’ve seen over the years, as well as some of the client interactions. There is some scientific content in Body in the Paddock, but it is not veterinary focused. I don’t want to say much more for fear of giving away too much of the mystery.

Caroline: Body in the Paddock is the first of the Spud Isle Mysteries. Now that Fran has completed her first murder investigation, what do you think will be next for her? Have you started writing a sequel?

Karen: I have a few ideas for Fran’s next adventure. Currently, I’m working on the sequel to Breeding Trouble. Once that is complete, it will be Fran’s turn to get knee deep into another mystery . . . possibly literally.

Caroline: Have you always been a writer, or would you say that writing is more of a recent interest? When did you catch the writing bug?

Karen: I’ve been interested in writing since I was a preteen. Over the years I’ve tried my hand at writing plays, skits, nonfiction articles, and short stories. I started Breeding Trouble as a challenge to myself to write a full-length cozy mystery based on my profession. It was a huge learning curve, hence the seven-year timeline, but it was a lot of fun.

Caroline: What do you enjoy reading? Which fiction writers have influenced your own work?

Karen: I enjoy reading cozy mysteries, and not-so-cozy mysteries, as well as general fiction, science fiction, historical fiction, and biographies of both famous and ordinary people from the past. Some of my favourite authors are Carrie Stuart Parks, Mary Higgins Clark, Alexander McCall Smith, Christy Barritt, M.K. Dean, Jayne E. Self, and of course, Lucy Maud Montgomery.

Caroline: What advice do you have for other writers?

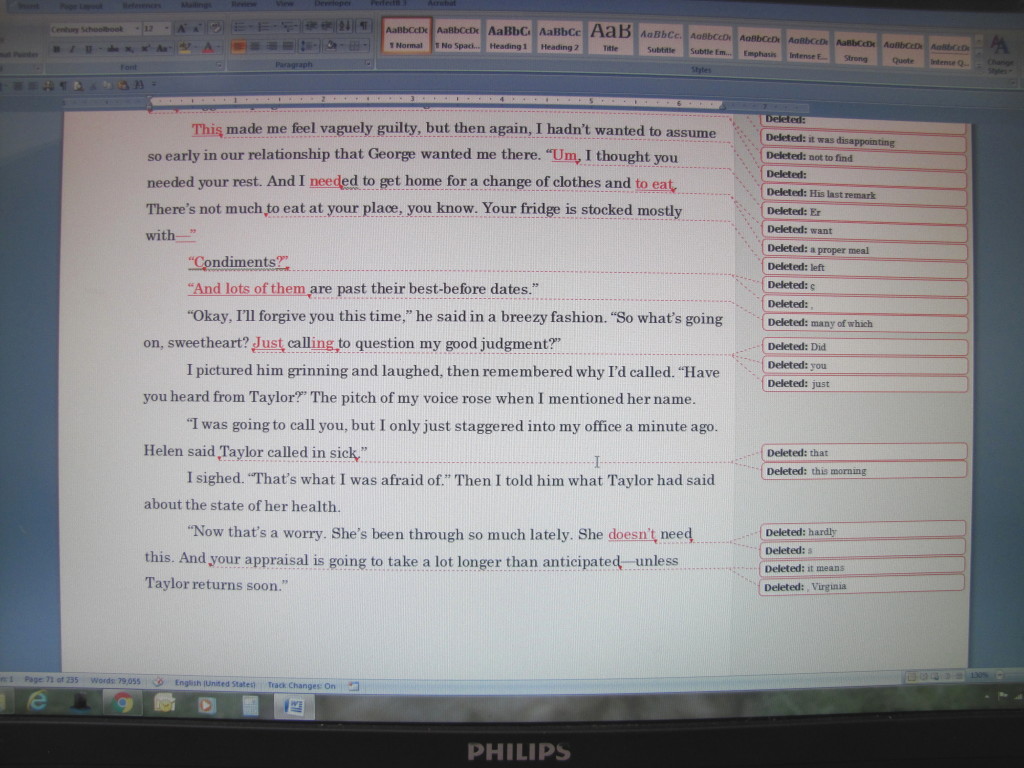

Karen: Write for the fun and experience, not fame and fortune. Your family and friends love you, so if you are looking for an honest critique of your manuscript seek out the opinions of strangers. I found it helpful to enter my manuscript into contests that provided constructive feedback. Learn from the critiques, but do not let them discourage you. Don’t get bogged down by all the “rules” on the internet—there are many styles of writing and many personalities of readers. Once your first draft is finished, hire an experienced editor to fine-tune your manuscript, and to give you an honest opinion. I have worked with two editors, and I have learned valuable lessons from both of them.

Caroline: Where can readers buy your books?

Karen: Both of my books are currently available on Amazon.

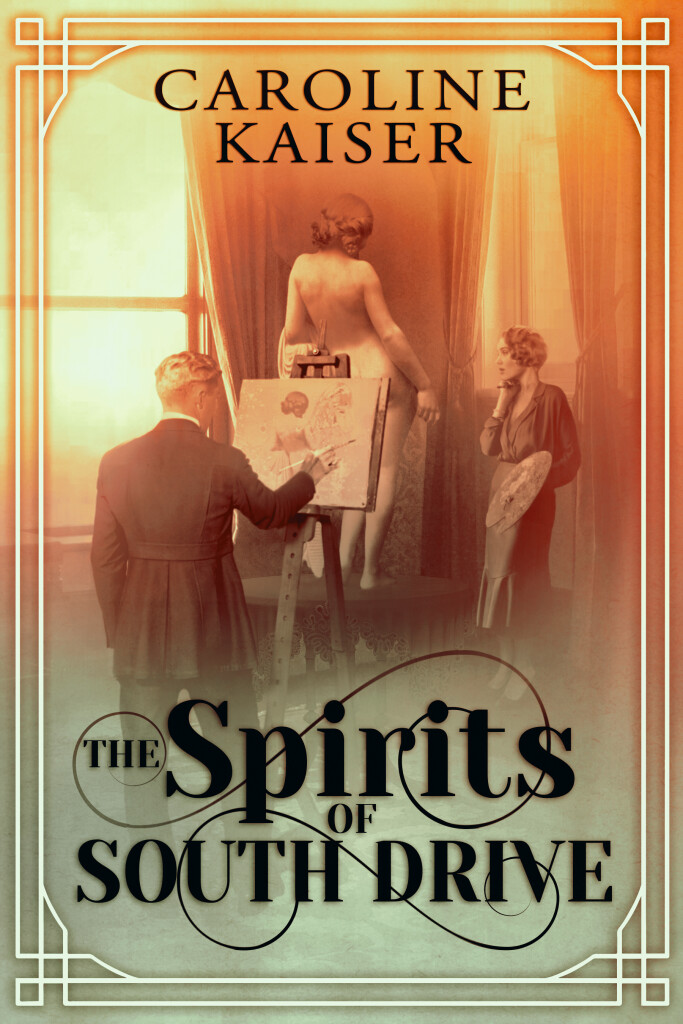

Louise Miller Mysteries: Breeding Trouble

Spud Isle Mysteries: Body in the Paddock

Follow

Follow