Virtually every manuscript that’s crossed my desk for editing in the past year or so has contained errors in the use of the homophones peak, peek, and pique. Personally, I’ve never had any difficulty keeping these three little words straight, but given the number of errors I see it’s obvious they’re a source of confusion to writers everywhere. I’ve seen “peak my curiosity” and “a sneak peak” among other misuses. Here’s a quick peek (if you’ll pardon the expression) at the differences between these words and tips for keeping them straight.

Peak is a word dating back to the 1500s, and it has several meanings as a noun. It can be the pointed top of a mountain or any mountain with a pointed top. Mountains aside, a peak is something that protrudes and reaches a point. When you whip egg whites vigorously, they end up having stiff peaks (and you’re then ready to make a meringue). A peak is also a high point in a different sense; you can reach a peak of activity or achievement. For example, “Horace reached his peak as a magician.” As well, a peak is the point on a graph that reflects the highest point in terms of a physical quantity. The brim of a hat (particularly in Britain) or the narrow part of a ship’s hold are also definitions of the word peak.

As a verb, peak means to reach an apex, and often a certain time for this occurrence is specified. You could say that “Horace peaked as a magician at age thirty.” Peak is also an archaic verb from about 1600 meaning to become sickly. Derived from it are the adjectives peaked (always pronounced pea-ked) and peaky, which is more commonly used in Britain. Both words emerged in the early 1800s and not surprisingly mean pallid or gaunt from illness. Peak used as an adjective is fairly recent, dating to about 1900. Again, it’s related to attaining a maximum. “Horace reached his peak level as a magician.”

Peek as a verb means to glance quickly or slyly. For example, “Alice peeked through the window at her devastatingly handsome neighbour.” It can also mean to protrude very slightly so as to be barely visible, as in, “His fingertips peeked through the ends of his threadbare gloves.” As a verb, it’s very old, dating back to the 14th century. It wasn’t used as a noun (meaning a quick or furtive look) until the middle of the 19th century.

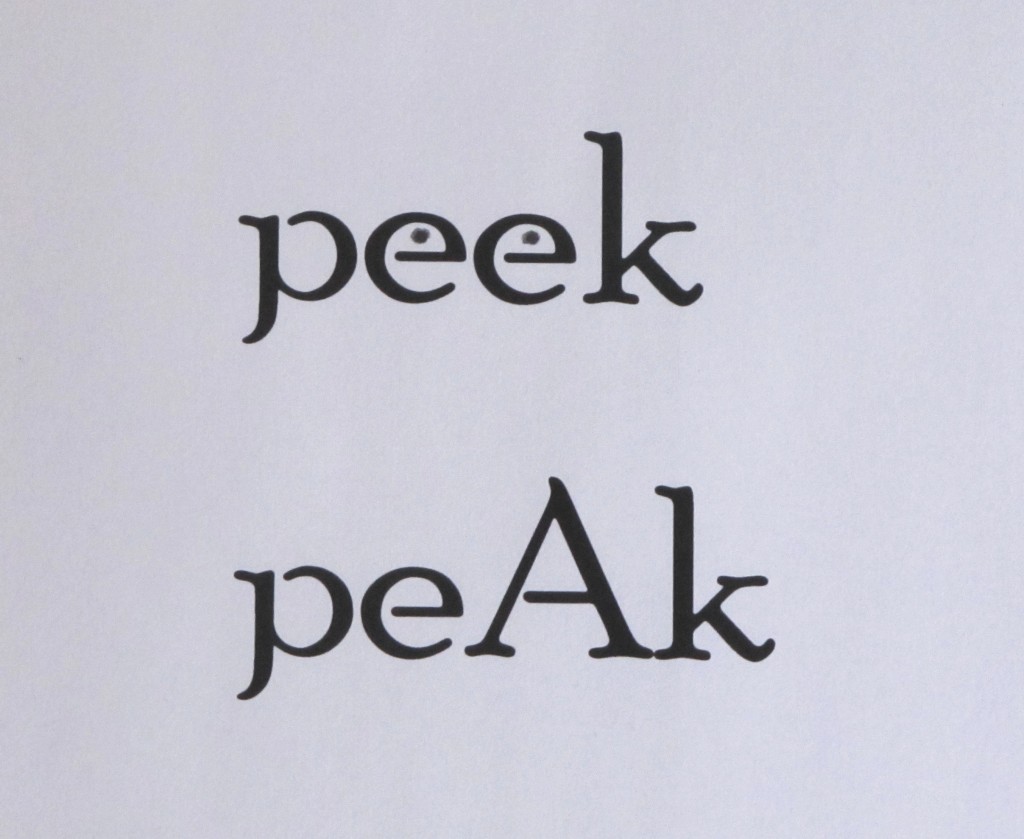

The important thing to remember about peek is that it’s always associated with looking, whereas peak is primarily associated with high points. With this in mind, I created this illustration to help you distinguish the two. The two es in peek resemble a pair of eyes, while the a in peak, when capitalized, resembles a mountain.

Finally, there’s pique. The word derives from the French verb piquer, which means to prick or irritate. The noun form of the word emerged first around 1600 and means irritation or resentment at suffering a slight or blow to your pride. A person typically has “a fit of pique,” which isn’t much fun for those witnessing it. But pique is most commonly used as a verb meaning to arouse interest or curiosity, and it’s been used as such since the late 17th century. For example, “You piqued my curiosity when you started whispering.” To be piqued means you’re feeling irritable. To pique yourself means that you pride yourself, but this is an archaic usage that’s unfamiliar to most of us. Pique is also used a both a noun and a verb with reference to piquet, a card game for two, but most of the confusion writers experience isn’t related to this usage. To avoid confusing pique with the other homophones, remember that it’s the only one with an i in it, which stands for irritation.

I hope I’ve clarified the meanings of peak, peek, and pique for you and provided useful tips for keeping them straight. Now when you need to choose the right homophone in your writing, you’ll no longer experience confusion or succumb to fits of pique!

Follow

Follow